Warning: this post talks about some distressing historical events. I will leave out the really disturbing details, but I leave it to you to decide whether or not you want to skip it completely.

We have seen many nagas on our travels through Cambodia. Representing prosperity, they adorn many stupas and temples with their blessing and protection. In this Buddhist pagoda we can see two serpent heads, looking out over from the two visible corners of the lower roof. Meanwhile, four naga tails flute out from the very top of the pagoda, rising high into the tropical sky. I’m no expert, but maybe they reach out to offer a tender touch to the world of spirits.

Up in that corner below the roof, spreading its wings, is a garuda, a mythical bird of Hindu and Buddhist tradition. There are four of them, too. You also see many garudas around, and it’s often shown holding a naga above its head in triumph. The truth is, they don’t get on. But here, on this pagoda, garuda and naga agree to appear alongside each other, in the spirit of peace.

To explain why, we have to introduce a third mystical beast – the Elephant in the Room that’s been overshadowing our travels, as it must do any visitor to Cambodia.

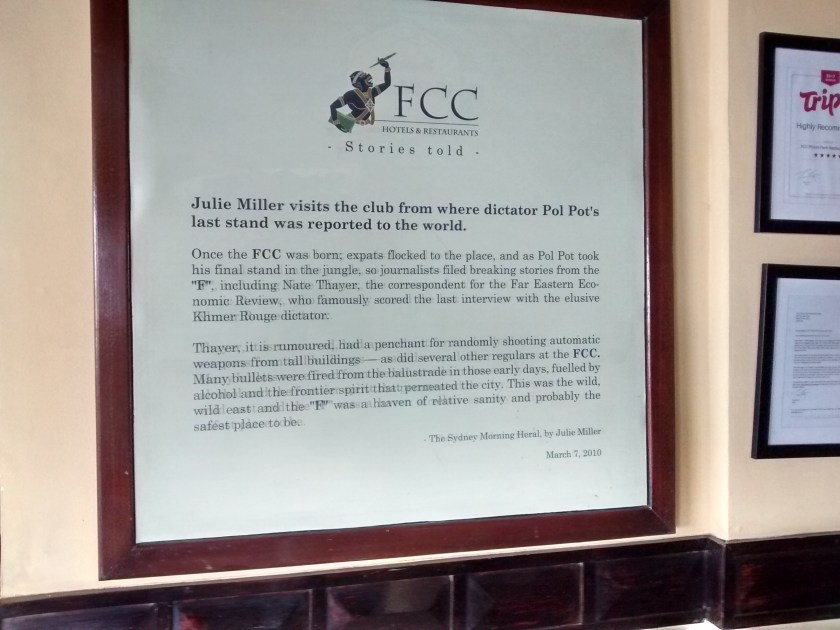

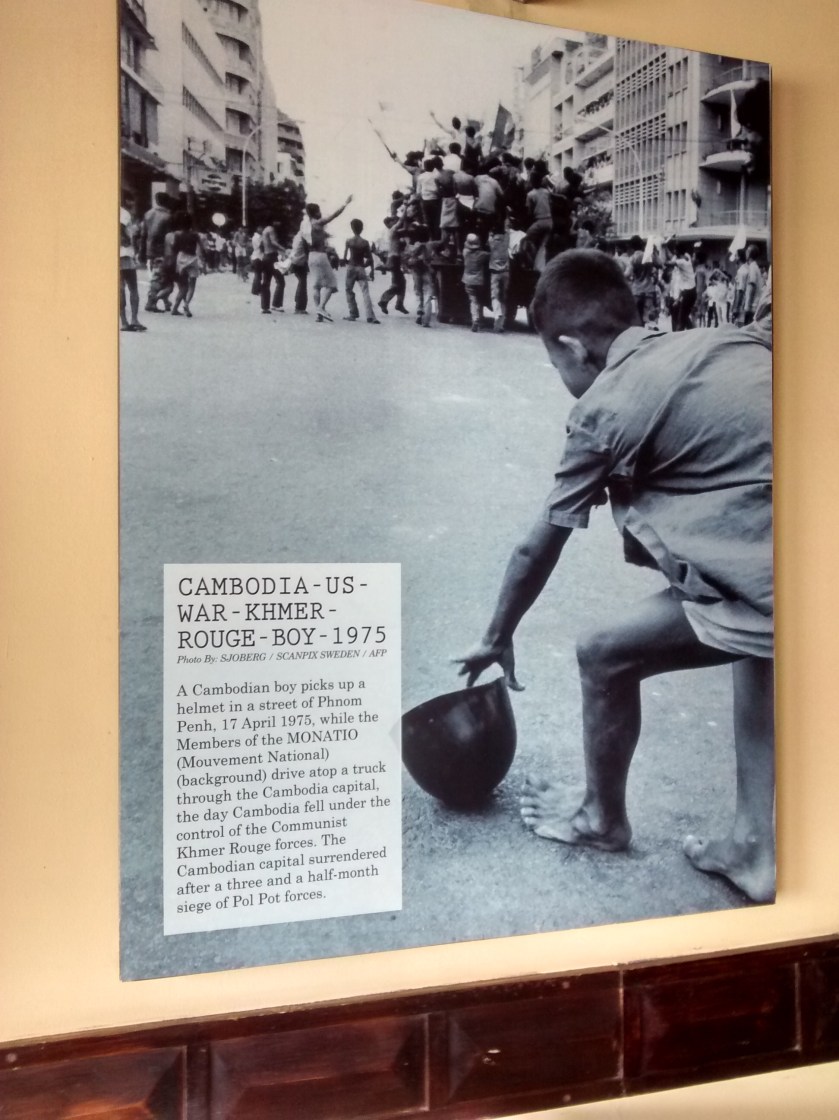

When the victorious forces of the Khmer Rouge entered the capital in 1975, they found a city swelled with many refugees from US bombing in the rest of country, which itself claimed 100,000 lives and drove many people to the side of the conquerors. So when the population was told they had to evacuate Phnom Penh for their old safety, people believed these then popular liberators who’d saved them from the corrupt Lon Nol regime.

It was a lie. The leader of the Khmer Rouge, Pol Pot, held to an even more extreme version of Maoism than Mao himself. To him the only worthy person was a peasant, the “old” or “base” people. The idea of the city, its institutions, its schools and hospitals, its culture, was capitalist decadence and had to be destroyed. Cambodia had to start from scratch, a nation of the base people. The citizens of Phnom Penh were being forced out into the countryside to work the land.

What happened there, with its stupid production targets, non-farmers being forced to meet them, the fact that the Khmer Rouge leadership didn’t have the foggiest idea how to run a country, is not our story – although that story led to a famine that is thought to have cost two million lives.

Our story is about the people the regime really didn’t like.

Tuol Sleng was a school before the Khmer Rouge came into Phnom Penh. Before long they turned it into a prison to hold political opponents and members of the old regime. Nothing new there, that’s what most dictatorships do. But it didn’t stop there. Soon, being considered a traitor and being a “new person” – urban, educated, intellectual -became one and the same. People were being rounded-up for such unspeakably imperialist crimes as being a doctor or a lawyer, wearing glasses, having soft hands (not the hard hands of a labourer). In the climate of terror some people offered false testimony against others, sometimes in their own family, just to avoid arrest themselves.

Judicial process? No need. Angkar, the name the regime gave itself, could never be wrong. So if they suspected you, then you must be guilty. And, oh yes, all the lawyers were locked up as well. By the way, please don’t confuse Angkar, the group that destroyed Cambodia, with Angkor, the nation’s pride and joy. If it helps, put a W in front of both of them. And chuck an S at the end of Angkar as well.

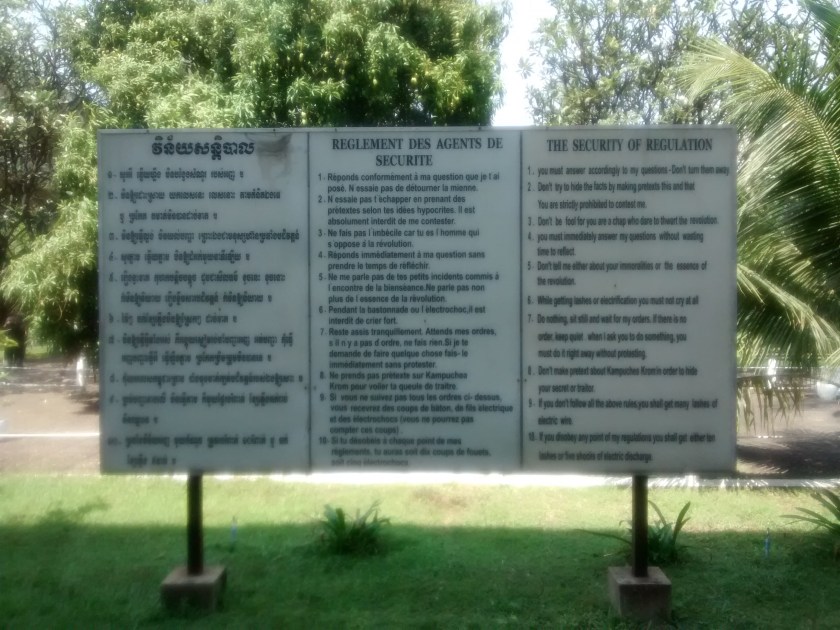

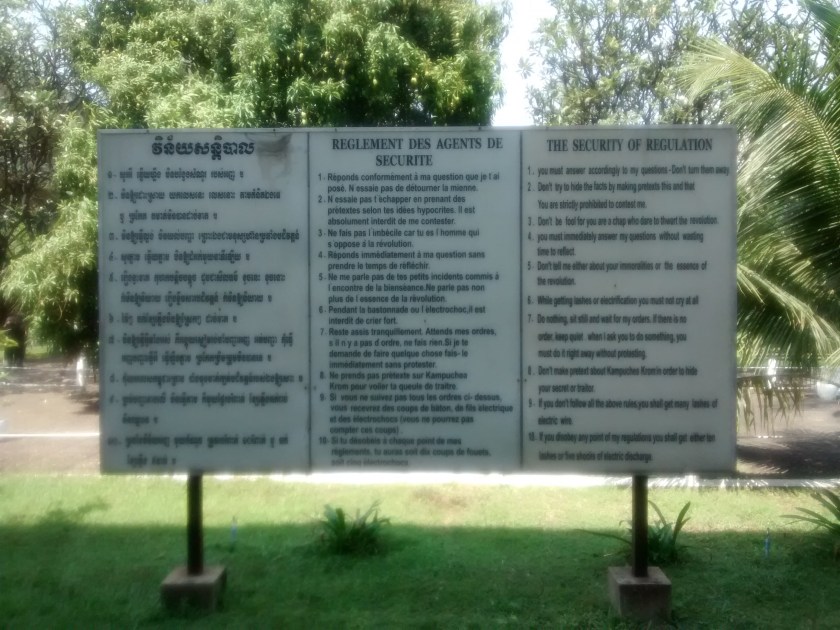

So you came here to confess your crimes, that you were working for the CIA or the KGB, or whatever, and then you would face the consequences. You could be held in a cell no bigger than a toilet, sleeping on the floor. Or you might be held in mass detention, 32 of you to one room, sleeping alongside each other on the floor. Then you were taken out for your barbaric torture.

The noticeboard mentions “chap”, but thousands of women were sent here too. And Pol Pot believed that if the enemy were a plant in soil, you had to take out its roots to stop it growing again. So whole families were sent here. Since 1980 Toul Sleng has been a museum dedicated to the memory of what was done here, and there are a couple of heartbreaking family album portraits of some of those husbands, wives, and children who were imprisoned here.

But there are even more mugshots taken by the authorities themselves of the prisoners, men, women, and many, many children. Some people look defiant, some scared, others bewildered, most resigned to their fate. It’s one of many things here that leave a lasting impression.

There are also photos of prisoners who were victims of “mistakes”, meaning they died during interrogation. They shouldn’t have. They should have completed their confessions! The photos were part of the investigations into what had gone wrong, and the interrogators would most likely end up on the wrong side of the cell walls themselves. (As did some of the senior Angkar leadership when the inevitable power struggles began).

Others avoided the misery by taking their own lives. The wire across the balcony in the earlier photo was to keep prisoners from jumping to their deaths. (The barbed wire in this one was as much as to keep people out as stop prisoners escaping)

It’s estimated that around 17000 people passed through here between 1975 and 1979, and there were similar prisons across the country. Fourteen unidentified bodies of prisoners were found in their cells by the liberators, and they are buried in the grounds.

Out of the 17000, only seven people that we know of avoided the inevitable step to Stage Two. One was an artist, another a plumbing engineer – skills the prison authorities found useful. The artist’s harrowing depictions of torture and murder are also on display here.

Stage Two. Once you had been dealt with here, you were driven 20 or so miles away to an old Chinese cemetery outside the city at Choeung Ek.

The Killing Fields.

Trucks would arrive from the prison two or three times a month at the beginning. Later on, they came every day. All the buildings have gone now – including the wooden rooms when you were held overnight before they killed you. Bullets were expensive so they used other means.

For example, can you see the sharp, serrated edges on the leaves of this sugar palm? Hammers, knives, machetes etc, also came in handy.

The butchery took place at night, revolutionary music blaring out so that the neighbouring villages couldn’t hear the screams. Sometimes they’d kill 300 people here a day.

You were either killed in what would be your mass grave, or your body flung into it. They kept consignments of DDT here to throw into the pits to finish the job – and to deaden the stench.

Men, women, children, babies…killed and buried in mass graves all around here. And imagine the same thing, repeated across the country.

The truth is, they don’t normally get on. But here, on this particular pagoda, garuda and naga agree to appear alongside each other, in the spirit of peace.

Because this pagoda at Choeung Ek is dedicated to the memory of all who died here – particularly to the 5000 whose skulls are piled high within its walls.

And, maybe, those high fluting tails of the nagas are reaching out to us, too. For, as the superbly- and movingly-narrated English audio guide, from whom I draw for this post, reminds us (delivered by a Cambodian who himself lost five of the nine in his family), this has not just happened in Cambodia. It has, and could happen anywhere.

And why not, at a time when the educated are derided as “experts”, lawyers once again as “enemies of the people”, when 52% condemn 48% as denying “the will of the people” and call for saboteurs to be crushed, where 48% condemn 52% as ignorant racists destroying the country and hurl their own accusations of treason, where authoritarianism and populism, fuelled by paranoid suspicion and fear, is gaining ground again across the world?

Why not?