Onto the No.50 bus we jump, one of the “Purbeck Breezer” buses that takes the summer tourist across and around the Isle of Purbeck peninsula.

Unfortunately, bad planning regarding where to join the bus in Bournemouth meant that I found myself at the back on the lower deck, not the best place to take snaps of the deep chines of Bournemouth, the harbour at Sandbanks, or the chain ferry that takes the bus over to Studland and the dramatic scrubland and rolling dales of Purbeck. (If you’re coming to Bournemouth, join the bus at the train station. It’ll guarantee you a seat on the open top deck. Make sure it’s not raining).

After the stunning scenery you’ll have to trust me about, the bus terminates at the charming beach town of Swanage.

Lovely. But there’s no time to waste, this isn’t our final destination today. To get there we’ll need a train.

“But”, you say, downloading your Network Rail route map, “the South Western Railway service between Bournemouth and Weymouth doesn’t have a formal scheduled connection to Swanage! What are you talking about?”

I’m talking about steam.

Swanage used to be joined to the main line at Wareham, and the branch line managed to survive the Beeching cuts of the mid-60s. But it did not survive 1972, when British Rail came to the genius decision of closing the branch line. When we see our final destination you will continue to scratch your heads – you may even start to draw blood. Just be careful.

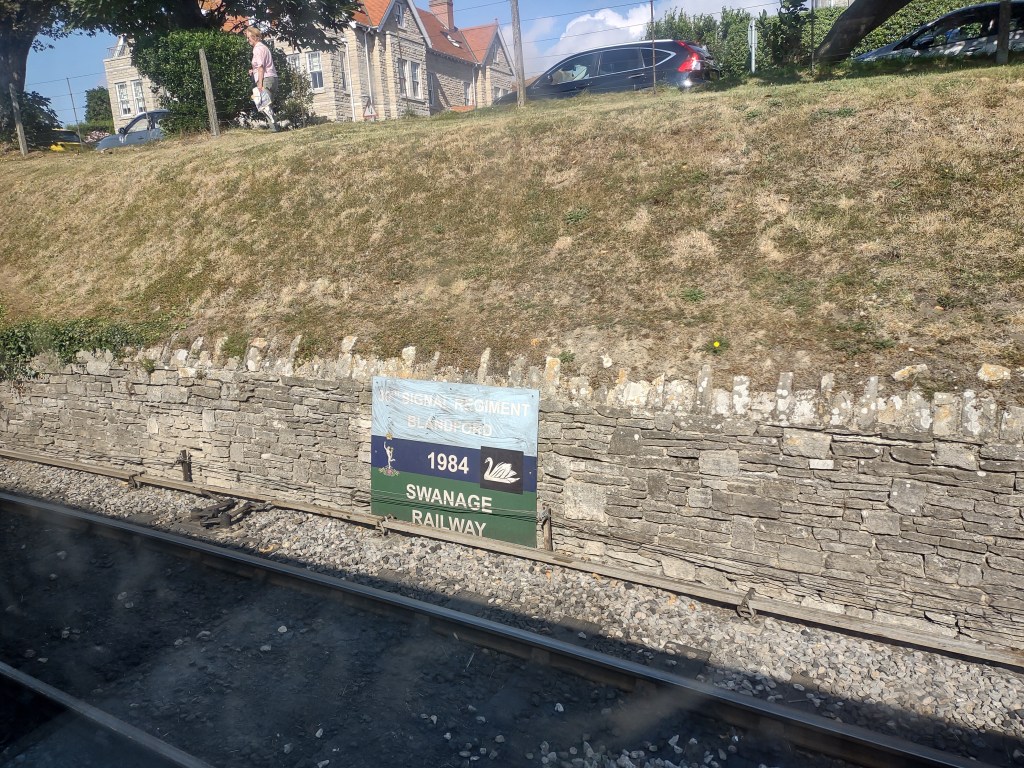

Almost as soon as the decision was made, opposition grew. A campaigning group was formed to keep the line open, even just as a heritage railway, and they fought BR all the way. When the track was pulled up, the campaigners made sure it was set down again. When British Rail tried to sell Swanage station off to a property developer they got the local MP onside – and kept it open. Slowly, the tide turned. The volunteers re-established old stations and even built a couple of new ones. They also procured and restored old locomotives and rolling stock. And they won!

In 1995 the Swanage Railway ran its first train from Swanage to the restored station at our destination. And in 2002 the connection to the main line was re-made, thirty years after British Rail closed it. Today the Swanage Railway, an all-volunteer operation, runs a scheduled service from Swanage to Norden, mainly powered by ex-British Railways steam locomotives with old-style slam-door C1 carriages.

Of course, if you tried the railway out for yourself you might conclude the train actually goes from Swanage to 1953. All the platform staff are kitted out like the porters from Brief Encounter, and they serve freshly-baked cake at the station. (Improvement.) From the restored station signage to the retro posters, it feels like a retreat to that famous golden British past that may or may not have existed (half of the general information boards at the little museum at our destination describe the history of the line in the two World Wars). The only thing that is missing, you might think, is a Brexiter joyfully buzzing the place in a Spitfire.

What do I think? Too late! we’ve reached our destination.

Which is…

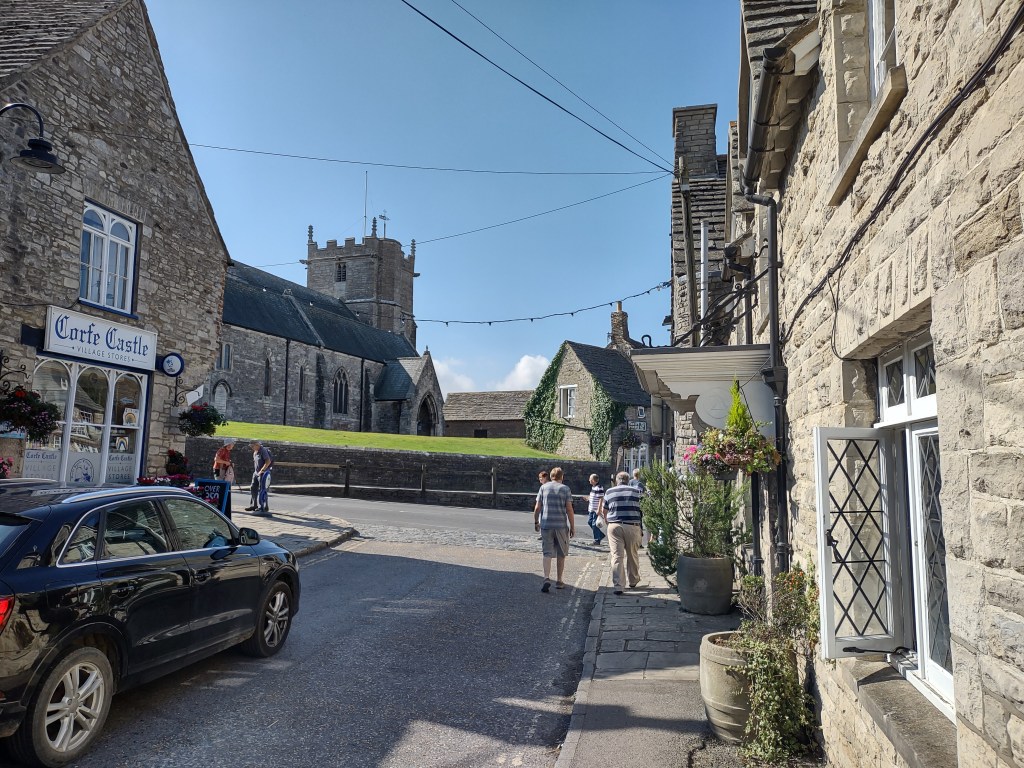

Corfe Castle is one of the most famous and romantic mediaeval ruins in the country. Built by various Norman kings on the site of an earlier Anglo-Saxon fortress, the castle is actually an outlier among British castles in being located atop a commanding height. In this case it controlled a gap between two lines of Purbeck hills, in the times when this part of the coast provided an invader with a decent backdoor route into England.

The three-storey central keep was started by Henry I and subsequently added to by his successors, and they turned it into a highly-desirable place for them to stay when passing through the region.

You can imagine the work that went on to build and maintain the property – the masons, the diggers, the bricklayers, later on the painters and decorators, all rubbing shoulders with the monarch and their lords and ladies of court…maybe even the cleaning ladies who were once paid to spend four days giving the place a good scrub.

It wasn’t all fun though, the Middle Ages in England were turbulent times. Corfe Castle had to withstand sieges and it was used to hold hostages from time to time.

Another typically beautiful view of the Dorset countryside, this time from the Butavant Tower. Around 1206 when King John took his niece Eleanor hostage, 22 of her loyal French knights were lucky enough to stay in this tower. Unfortunately, I don’t think they got to enjoy the view. Or the dining options, it turns out, as King John had them dropped down a pit into an oubliette, a special dungeon where you leave the guests to rot (oublier : forget in French). So the reception desk forgot about them and they all starved to death. (The records do not state whether or not they were ABTA-protected.)

Surprisingly, it wasn’t all those mediaeval dynastic squabbles that left Corfe Castle in ruins.

Elizabeth I sold the castle in 1572 and eventually it ended up in the hands of the Bankes family. If you own a big property like this, you have to take all sorts of things into consideration; upkeep and maintenance, general estate management and security, not being on the Royalist side during the English Civil War and forcing the Parliamentarians to try and take the castle by force, marketing the castle to tourists, that sort of thing. The Bankes family got at least one of these wrong.

When Cromwell’s forces finally took the fortress in 1645, they were so impressed by the resistance Lady Mary Bankes, the owner, had put up, they gave her and her family free passage out. How nice. Then Parliament voted to blow the place up. And that was it. Much of the Purbeck stone used to build it ended up lining the walls in the village of the same name down the hill.

Well the Restoration came and the Bankeses got it all back, but they’d had enough – who can blame them! – and set up shop in Kingston Lacey. In 1981 a descendant bequeathed the whole place to the National Trust, with whom it remains – an evocative, fascinating, rather sad testament to the brutal but compelling story of these islands. That we can all agree on – unless we’re British Rail in 1972.

That reminds me, time to get back down the hill and get the train back to Swanage. Back we go to that rather marvellous full-size Hornby train set…

…and back to Swanage, the bus, top deck this time, and some final views of Poole Harbour from Shell Bay.

Well, you know you might prefer your 1950s Britain, or your 2020s Britain, but aren’t we all learning to discover and appreciate Britain itself, whichever year we fancy? I know I am.