Liverpool – oppressed, defiant, emotional, wild-hearted Liverpool – has a number of spectacular places of worship that seem to capture the passion and ambition of the city. Let’s visit the four most significant ones.

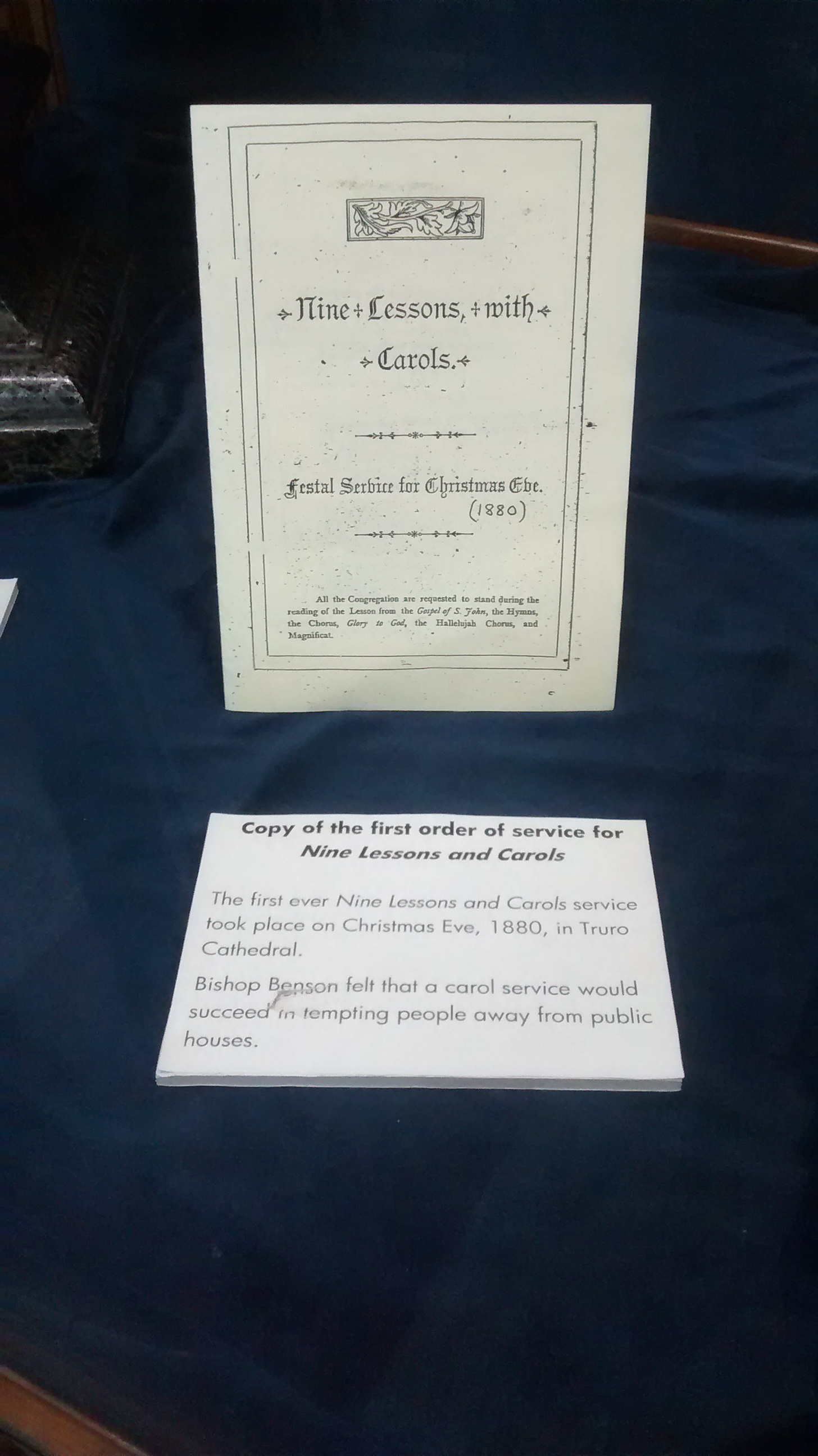

As the city expanded in the 19th century, the many parish churches around the town just weren’t sufficient to host the growing congregations. The Church of England thought their main church “ugly and hideous”. So they were first up and set about requesting submissions for a new cathedral. It would be only the third new CofE cathedral built after the Reformation (St Paul’s and our old friend Truro being the others). And it was Liverpool so it had to be enormous.

The winner was a young architect called Giles Gilbert Scott with his Gothic design, and the foundation stone of Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral was laid in 1904. Scott was very inexperienced so it’s a mystery how this scion of a famous line of architects, whose famous architect dad was an in-law of one of the judges, had got the commission. Scott then changed his design in 1910 and it all had to be resubmitted for approval. Then there was a war. Then they started again, aiming to complete by 1940. Then there was another war. Then they had to fix the bomb damage. Then Scott died in 1960 (having also come up with the red telephone box) and his son took over the firm. Eventually it was all done and officially opened in 1978.

But if the customer contract stipulated “has to be absolutely ginormous and you have to be able to see it from everywhere”, well, tick in the box. At 189 metres from west to east, it’s the longest cathedral in the world. By volume it’s the fifth biggest. They even put it on a hill just in case you missed it the first time. Nice of them.

Don’t have nightmares.

I managed to get inside a couple of days later. Fair to say, it hadn’t shrunk.

So that was the Anglicans sorted. What about the Catholics? Hundreds of thousands of Irish migrants poured into the city in the 1800s, and the Catholics amongst them needed their own new cathedral. And it had to be Liverpool-big too. Step forward the great Sir Edwin Lutyens and his plan to build the second-largest church in the world, with the biggest dome. And it was also going to be on a hill, at the other end of Hope Street to the Anglican Cathedral that it was meant to rival.

Work on the Metropolitan Cathedral started in 1933. Then there was a war. Then Lutyens died in 1944, surrounded by his drawings. When work restarted they only managed to finish the huge crypt before they realised they were running out of money. So they wiped the slate clean. The new architect, Gibberd, came up with something a little more space-age, a main circular space under a conical roof with Thunderbird 6 sticking out of it.

The Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King. Also known as “Paddy’s Wigwam” or “The Pope’s Launching Pad”. Scouse wit. Also known as “The Funnel”. Scouse practicality. Started in 1962 and finished five years later, eleven years before they finished off down the road. But act in haste…the church ended up suing Gibberd because bits of it leaked.

The four bells on that concrete screen at the front are known as Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. To the clergy, that is. Guess who the locals name them after. Hint: this is Liverpool.

Two great Liverpool cathedrals done, two to go. I went to the other two places earlier in the day, catching the bus from the city centre to the idyllic Stanley Park.

Another ginormous place of worship arising above the rather dilapidated housing all around…

They were formed in 1878 from a local church team, and moved into this new stadium in Anfield in 1884, winning their first League title in 1891.

They, of course, were and still are, Everton.

The ground was owned by a man called John Houlding. Everton fell into a messy legal and political dispute with him, and in 1892 Houlding had a right hissy fit and created his own team, Liverpool FC. Everton responded by taking their ball away – literally, striding the ten minutes walk across the park to a new site, on Goodison Road.

From here…

…to down there…

I’ve been following football now for decades and I feel I know so much about Liverpool and Everton, their history, their great players and the great matches they’ve played, the ups, the downs, the tragedies, the controversies – and yet I had no idea how tranquil Stanley Park could feel on a sunny day, as if everything that surrounds these teams – and football – didn’t exist at all.

Once you get down to Goodison, football truly reasserts itself.

Whereas Anfield sits in its own extensive grounds, Goodison feels more homely, closer to the street, almost like a large car dealership or industrial park.

And that’s a problem. Everton need to grow that stadium to be competitive with the truly big boys, and there’s no room here. So in 2024 they’ll be moving to a new stadium by the docks.

It’ll be sad to lose one of the great historic British football grounds, but it’ll also be sad to break the ties between Liverpool, Everton, and the park that divides them but also binds them.

And we’ll never get to see this view on Match of the Day…