Alicante then.

An extremely pleasant place to spend a few days, a mixture of beach holiday, old town wandering, castles, cervecarias, museums and whatnot. It doesn’t have quite the range of sights as a Valencia or a Málaga maybe, but you’ll always find enough places to go to keep you occupied. And as we’ll see, there are some compelling stories to uncover away from the beaches.

It turns out that Alicante’s Rambla doesn’t quite have the exciting nightlife options of Barcelona’s, it’s really just another thoroughfare in the centre of town, chock-full of the usual Spanish and international shopping outlets, some eateries, et cetera. Still a good point of orientation as you climb away from the beachfront and into the main town. Which is what we’re about to do.

Alicante followed a similar historical path to many cities in these parts – Roman, Visigoth, Arab Muslim, Christian Reconquest, various dynastic wars, Civil War. In the meantime a port developed under the Arabs and hit the boom times during the Golden Age of Spanish empire. That there by the way is the Castell de Sant Barbera, built by the Arabs, maintained and fought over during Christian times, essentially dominating the city and the region, high up on the Benacantil mountain.

You can’t miss it.

Where there are temples to power, nearby you usually find temples to even higher powers, and at the bottom of the outcrop there used to be a mosque. When the Christians took over it was bye-bye mosque and over the ruins they built Alicante’s main church, the Basilica de Sant Maria.

There must be something obvious I’m missing. How do you get in to have a look at the churches here? Whenever I’ve turned up they’ve all been closed. Except for Mass, and it would be rude and disrespectful to take lots of pics then.

So it also seemed for the Co-Cathedral a bit further down, but it does offer some fascinatingly-austere external shots.

Up we go, past the Mercado, and we reach the monument dedicated to one Trini González de Quijano.

Quijano was the local governor in 1854 when cholera broke out in the fast-growing city. He became famous for his tireless efforts in helping the sick – sometimes cradling them in his arms – while making sure medicines were free, shopkeepers didn’t speculate, and priests didn’t run away. We’ll see how he got on a little later.

On we go.

Another closed church! This time it’s the Parish of Mercy. Completed in 1752 to care for the poor, and 1900 would see it open for wandering travel bloggers like me.

That’s 1900 as in “7pm”. Aha! Maybe it’s the same for all the churches here.

You may be wondering, it all looks lovely and all that but it’s kind of, modern-looking for 1752? Good spot.

In my last post about the Italian Fascists bombing the market during the Civil War, I rather gave the populist far-right a bit of a kicking. If you’re a bit of a far-right populist yourself I apologize for offending you and to try to make up for it, here’s some balance.

The port city of Alicante had a rather liberal, open-minded view on things dating from Napoleonic times and naturally it sided with the Republicans during the Civil War against Franco’s Nationalists. However the Republicans weren’t exactly squeaky-clean santos themselves. Their coalition included communists and extreme anti-clerical groups, whom the liberals struggled to control. Atrocities were committed on both sides, and for the hard left the Church was in the firing line – literally. Many churches in Alicante were destroyed and this one had its main altar and its chapel knocked about.

I hope that makes everything clear. If nothing else my blog strives to be fair and balanced, a good read whatever your opinions may be. Anyway, the temple we see today was inaugurated in 1952, as the Spanish church regained its status and power under Franco – who had by then had his opponents locked up in concentration camps, abolished democracy and emboldened his mate Hitler to see how far he could take this genocidal fascism thing. Yes. Fair, and balanced.

A lovely little Spanish place, the old Post Office. It’s not on our route, I took the pictures a day or two before but I thought I’d throw it in to raise the mood as it all just got a little…heavy. Evocative of Spain, I thought at the time, but it was only when I reached the next part of today’s tour that I felt I’d finally reached the heart of the country, with probably the first aspect of Spanish culture that I was ever aware of as a child.

Bienvenido, one and all, to the Plaza de Toros. The bullring.

And all of a sudden Spain begins to feel more alien to the English-speaking visitor, more deeply spiritual, more – more Spanish?

Spain, like many places, has become more and more conscious around animal rights and some cities have banned bullfighting. Not in Alicante. There’s a museum here but this is still an active stadium, tickets going for over 100 euros for the best i.e. shaded seats. According to my limited Spanish comprehension there was due to be another session this weekend.

They give you an audio guide for the stadium tour and, whatever your views on the sport/”sport”, I’d thoroughly recommend it if you’re staying here. It’s a revelation. (Best not come if you have problems with mounted bulls’ heads though).

The Plaza de Toros, with its fine Mudejar-style interior, dates back to 1847. Forty years later it was renovated by another local architect, José Guardiola Pico, who added a second terrace. The bullring now holds 14000 people. You could say senor Guardiola gave the place a proper, ahem, pep-up.

But hurry! the toreadors are nearly ready, the bulls are feeling bullish, it’s showtime baby!

Before the corrida, say a prayer. Just in case.

The last stop before the matadors head out into the ruedo is a tiny chapel on the concourse. Here they follow the advice offered in this old bullfighting proverb, maybe honouring the figure you can just see on the wall of this little room. And suddenly you remember that this is a deadly occupation, for toreador as well as bull, a challenge and an opportunity for both sides of the swishing cape to show their bravery and face the fatal possibilities with nothing less than dedication, nobility, and honour.

The image on the wall? It’s the Santa Faz, the Holy Face of Alicante, a much-revered icon of the city. Created when a woman called Veronica wiped the face of Christ on his way to his crucifixion, the cloth made its miraculous way to Venice, which it saved from the plague. In the 15th century a priest from hereabouts was in Rome when he was given the Faz. (Wikipedia says nothing about how the Romans felt about losing something so utterly useful – let alone the Venetians)

At this point the story becomes real to me. You’ll have noticed that I travel a lot. So that means a lot of packing. And unpacking. It can be a right pain when the bag doesn’t close, or when you actually need those clothes you left at home because you thought you might need the space. (Not to mention that time I left my pyjamas in Cologne). It’s always helpful to have a system, where to put the socks, the undies, how to roll the trousers to make them fit, etc. Father Pedro Meno’s carefully-designed system involved putting the Santa Faz in first, and then putting everything else in on top. So Padre Pedro, wherever you are, I can sympathise with how you must have felt as you did your pack, headed back to Alicante, and at every stop you opened the bag and found the Santa Faz had made its way to the top.

After stopping a drought on the way, it reached Alicante and a church was built to house it, the monastery still stands. Over time such was the devotion that people started taking strips of it and they had to do some reconstruction and stick it in a reliquary. Meanwhile look closely around the city and you should see depictions of it – like the one here.

On the walls here we get a close-up of the Mudejar tiling. The Mudejar style is essentially a continuation of the Islamic style from the Moorish era. For example, there are no human forms on the tiling, they are instead a riot of geometric form and the stylistic imagination.

And so another layer of Spanish identity reveals itself, or maybe multiple layers. The scene is unmistakebly Spanish, but the scene of Catholic devotion inside might have happened in Sicily while the wall tiling outside could be in Samarkand.

No time to ponder, we need to go somewhere else. Because prayers aren’t always answered, and bulls are dangerous.

Incredibly, according to the audio guide the stadium infirmary is the oldest such medical facility in the whole province of Alicante – stadium or not! And despite being something of a museum piece, and the tour allows you to go inside to take a look, it is still in use! It is possible that someone might be wheeled in here in future corridas. Touch wood that doesn’t happen.

The principal danger to the matador is being gored by the bull. At the time the audio guide was recorded the last goring at the Alicante corridas was 2016. Alicante has only seen one (human) death, and that was in the 1910s.

So suitably focussed, mind completely on the job, the toreadors enter the ring, in a procession suffused with meaning and symbolism, and there they go through entrance no. 2…

Good luck!

That just leaves the other stars of the show. They are penned in just along the way, waiting their turn…

Alicante is a Category 2 bullring, which means the bulls must weigh at least 435kg. Categories lead to all sorts of subtleties about what can and can’t be done, indeed the rules of bullfighting – the matador’s passes, the handkerchiefs of the ring president, what the bull must do to be allowed to live, etc etc – is so mind-bogglingly complex I invite you to do a quick G..gl. to find out more.

Because I’m off to my seat. It’s time for action!

Well that was fun. I think that guy there won.

A quick spin through the actual museum bit reveals lots of great photos, cloaks and other memorabilia of the greats who’ve performed here down the decades. Including this cloak.

One hopes that Santa Faz performed its magic and the toreador got out unscathed.

Incidentally, the stadium is also used for concerts and other sporting events. It even staged the Davis Cup semi-final between Spain and France in 2004. On the Spanish team that day was a certain Rafael Nadal. Considering the career he went on to have, do Fed, Nole, Murray and the rest ever wonder if someone should have checked Rafa’s bag that day? He might have had a face towel that, somehow, kept appearing at the top of his kit bag whenever he needed a new racquet…

Time to leave this fascinating and evocative place, controversial maybe but also storied, and with a touch of Mudejar grandeur to it, senor Guardiola’s second terrace resting proudly on that Moorish-influenced base.

You might even say, Guardiola could not have achieved what he did without support from the Arabs.

Out we go, back down again, back into town.

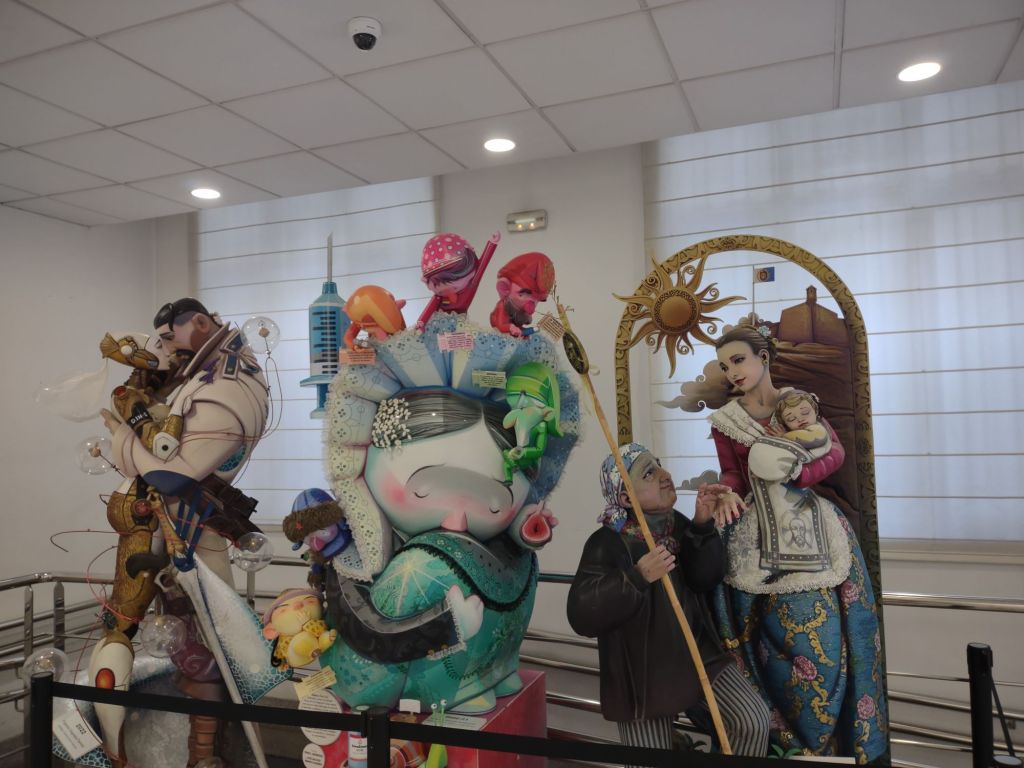

Like many Spanish communities Alicante celebrates the Feast of St John in June with a great fiesta of bonfire lighting. But here it’s the biggest event of the year. We’re now in the Museum of the Bonfires, which displays the specially-sculpted figures, or Ninots, that were so good they weren’t thrown into the flames after all. In fact there’s prize-giving for the best ones every year.

There are handy plaques around the museum describing how the Ninots developed over time, what they represent, and so on. They’re in Spanish, Catalan and English. I can read a little bit of “museum Spanish” but the English was so garbled, clearly G..gl. Translate at its worst, it absolutely did my head in and I just took a look at the figures for myself. I gathered that they were in general comical, satirical, historic, a little surreal and sometimes philosophical.

And sometimes just very weird. Maybe more so if you’re a visitor to this city, or maybe even if you’re a local. Still a bit of Charlie Chaplin will always lighten the mood a little.

Which is handy because the Ninots can be very sad as well.

Yes, sorry to say it’s our good friend, Governor Quijano. His battle to defeat the cholera epidemic was successful, but just as the plague was on the wane it seized the opportunity to settle a personal score. Exhausted by his efforts, Quijano succumbed easily. He was only 47 when he died. The monument we saw earlier is actually his mausoleum.

A heroic figure. And that’s something I think we can all agree on.