Most would call it “a week of sun, sea and sangria on the Costa Blanca”.

Me? I call it “unfinished business with the Spanish-speaking world”.

The knee injury from my last post had its complications, and it needed a second operation back home. Now I’m into a second bout of recovery and physio, and although the fix seems to have stuck this time anyone who has been through something like this knows that it takes a good while and a lot of work to get it properly moving again – whatever “properly” will mean in the future.

At the moment I still can’t do all the things I used to take for granted, or at least it takes longer to potter through them than it used to. The good news is that there has been good progress since the brace came off and I’m much more mobile than at any time since the accident. Touch wood, and anything else I can reach with my crutch (just the one now, and rarely used except for the odd step).

So I’ve been getting out and about a bit more recently, and being able to go to the normal places and see people again has been a thrill and reminded me that you only really notice the simple pleasures and joys of life once they’re taken away. That stuff has all been great. But (and I apologise if you’re one of the lovely people I’ve met up with in the last few weeks), there’s one activity that I was really hoping to do once it made practical sense. One thing that I love so much, I even started blogging about it…

Just two hours flying time from London, the sun-kissed city of Alicante is perfect for the rehabilitating traveller who had to let the wet, cold English “summer” of 2024 wash over them but is a bit worried about how their legs will get on in an economy seat (fine, as it happens). My thoughts had turned to this region not long ago after a friend spent a lovely time nearby – somewhere that wasn’t Benidorm!* – and in my research I discovered that Alicante looked a bit like Valencia and Málaga from last year – a vibrant, authentic Spanish city, great beaches, nice winding streets, a castle or two. So here I am, slowly getting to grips with it, and I mean slowly. It will take me a bit longer than usual to get a feeling for the place and have enough information about the photos I’ll be sending, so apologies if I repost a couple once I do a tour or two and get more information (yes, yes, I know I could just Google it all, but where’s the fun in that?)

*He says he didn’t spend much time in Benidorm, if any at all. I suppose we have to believe him

We’re looking inland from the marina at the moment, and we’ll cross the esplanade and head up into town via a little avenue.

Alicante is Alacant in the local language of Valenciano (it’s part of the Valencian Community). Valenciano is a distinct language, and previous research has led me to in no way confuse it with Catalan!

As in Barcelona, where they speak a completely-unrelated language, by complete coincidence a tree-lined avenue here is also a Rambla.

Fortunately no-one seems to realise you have lovely relaxing Rambla strolls in other spots on the Spanish Mediterranean, not just Barca. So it’s not as crowded.

Don’t tell anyone. I said nothing, Ok?

The Rambla climbs up to another centre of things, the Mercado Central, the market, the final stop on this opening blog post.

Built in the early 20th century to replace a rather rickety street market, the Mercado is still the place to get your local meats, your fruit and veg, maybe sit down to have a cervesa or two once the ingredients for today’s cena are in the bag. During the Spanish Civil War the Italian fascists so appreciated this temple to old-time indigenous European traditions and values, they did what the far right so love to do whenever they get the opportunity.

Kill as many people as possible.

At the back of the market is the Plaza 25 de Mayo, which commemorates the bombing of the market on 25th May 1938, and the 300 people who were killed that day.

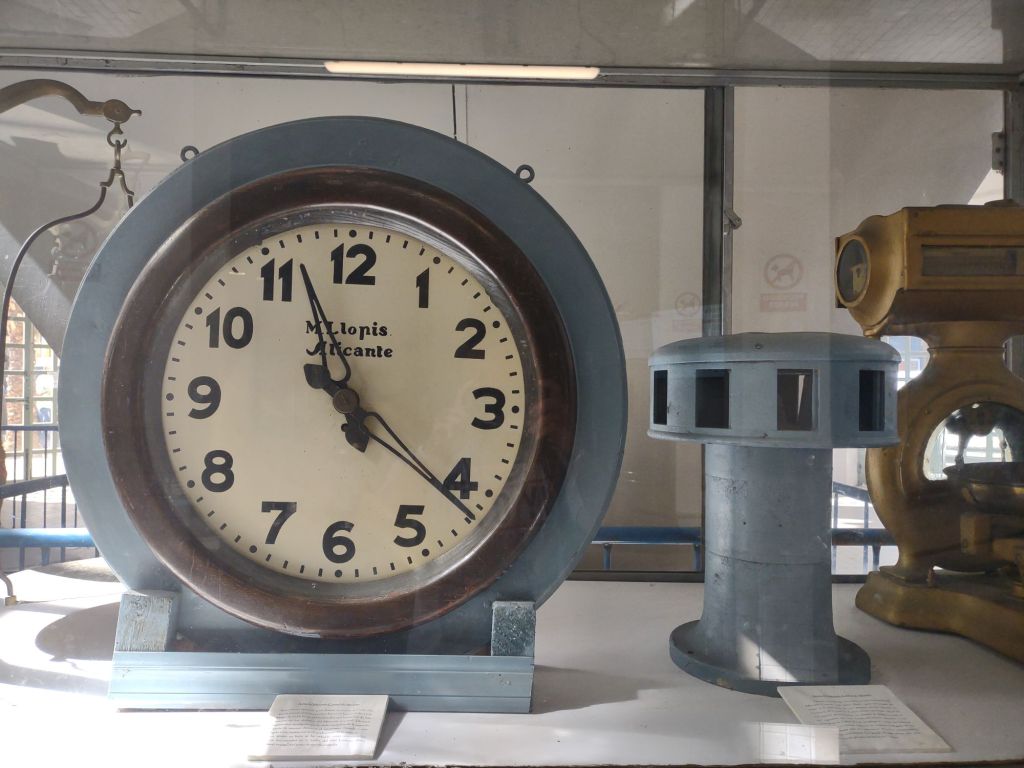

Alicante was probably expecting an attack, so much so that there were air-raid sirens in place. But some of them failed just when they were needed, and people were caught unawares. One of the sirens is kept in a museum case at the entrance, along with an old clock that stopped at twenty-past eleven that day.

The time of the attack.

Frozen in time, for ever. There have been moments this year that I’ve wondered if my personal clock of recovery has stopped. And if Europe’s own clocks are being re-wound back to the Thirties, as if the fascists are seeing their time come again. It looks like the hands on my own clock-face are moving again, gradually moving away from my moment of crisis.

But what about Europe?