Although the most well-known part of Vilnius is its atmospheric and charming Old Town, as a visitor your chief reference point will probably be Gediminas Avenue, the broad 19th-century thoroughfare that runs through the heart of the town. Lined with banks, ministry buildings, shops and food outlets, sooner or later you’ll find yourself on or nearby Gediminas Avenue.

Or should that be (St) George Avenue? (Tsarist Russian Empire)? Maybe Adam Mickiewicz Avenue (Polish occupation, post-1918)? How about Stalin Avenue (early Soviet Union) or even Adolf Hitler Strasse (Nazi occupation). Too much? Perhaps good old Lenin Avenue fits the bill (pre-independence).

As you can tell, the old joke about the Eastern European man who spent the 20th century living in seven different countries, without ever leaving his house, has some truth in this part of the world. Lithuania has had, and continues to have, a complex relationship with its neighbours, and sometimes it surprises. For example at one time most inhabitants of Vilnius were Polish (only 6% Lithuanian) and today over 50% are ethnic Lithuanians and 40% Poles. And that’s even before we get to the 4% ethnic Russians and the tensions there.

It’s a very deep story to develop satisfactorily in a little blog like this, and I’m heading home today, my short stay over. So the best I can do is give you a necessarily superficial view of some of the sites, the feel, the quirkiness of the place.

We start with a wander down Gediminas Avenue

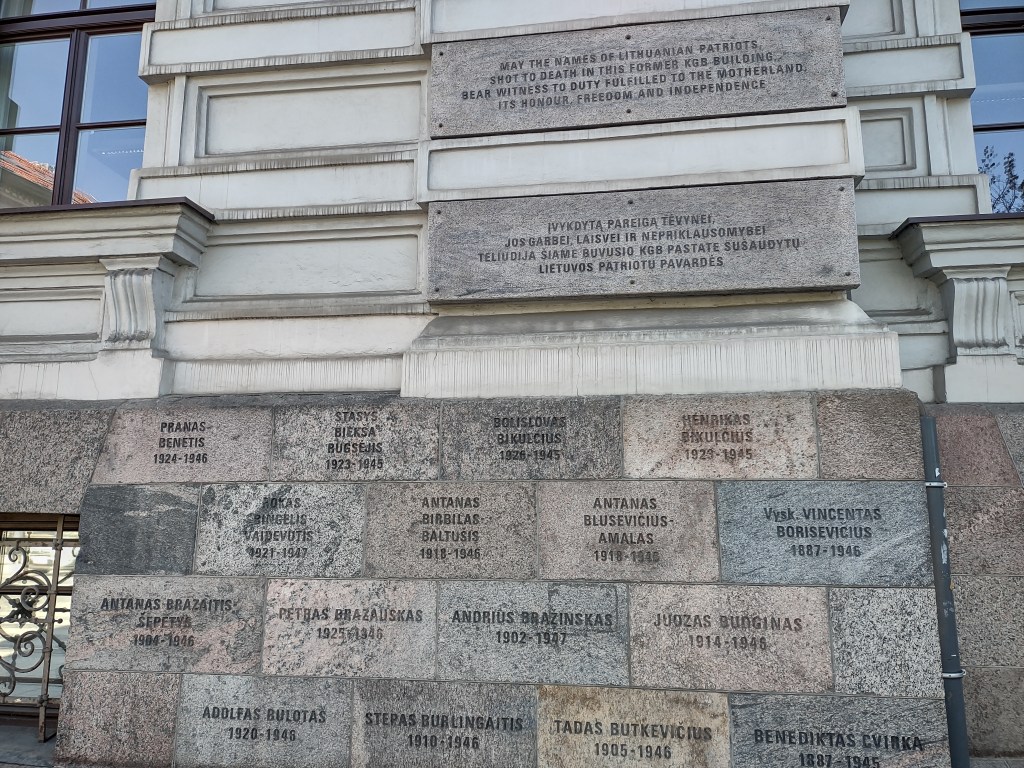

This innocent-looking building was indeed an innocent office block until Stalin took over and it became the local headquarters of the KGB. When the Germans arrived in 1941 they appreciated its heritage of torture and brutality and the Gestapo set up shop. The Soviets liberated the town in 1945 and down in the basement proceeded to “liberate” numerous local partisans from their lives. Their names are carved into the walls of the building, which is now a museum to its grim history.

I didn’t go in. Ironically, the museum dedicated to Soviet Communist oppression was closed for the May Day holiday.

On we go, down the street, past the odd statue…

…opposite the odd opticians…

..until eventually the Avenue gives out onto the great plaza that marks the centre of town, and probably the whole of Lithuania itself. Cathedral Square.

Vilnius is considered the most Baroque city north of the Alps, but the monumental Cathedral is a masterpiece of Neoclassisism. It’s been the spiritual heart of Lithuanian Catholicism since it was completed in 1783 – except for that period when the Soviets turned it into a warehouse.

The free-standing Bell Tower is all that remains of the old 14th-century castle walls that ran through what is now a square. The walls were torn down and the old battlement tower was turned into the cathedral’s campanile.

If you find this spot between the cathedral and the tower, your luck might be in. Legend has it that if you stand on it, turn around three times, and make a wish, that wish will come true. Stebukla means “miracle”. And the locals believe a great miracle did happen around here.

I am here to tell you I am old enough to remember the miracle. And if you are as old as me, you saw it too.

I’ll tell you later.

You’ve seen this one before. Cathedral to the left, to the right the rebuilt Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, and in front there’s good old Gediminas, and you can also make out that wolf. Behind and to the right there’s the park that leads onto Gediminas Hill with the ruins of the old castle. Let’s take a quick look.

Nice view of the Old Town…

…and over to the Hill of Crosses, marking the martyrdom of a number of Christian priests in the time when Lithuania was pagan.

Heading down, let’s explore the Old Town a bit.

Napoleon thought it was so lovely he wanted it brought back to Paris with him. Constructed at the end of the 15th Century, St Anne’s Church is a fine example of Flamboyant Gothic. Right behind it is the less-flamboyant Bernadine church.

The French were less keen on this one, so much so they used it as a battlement. Obviously Napoleon wasn’t a true sightseer, or if he was this was a short layover for him and his friends as they headed to their final destination in Moscow. The return journey wasn’t so comfortable though; there were no catering facilities on board and they couldn’t switch off the blasted aircon.

Nearby stands this statue of the great Polish romantic poet, Adam Mickiewicz. We mentioned him before, the big avenue was renamed after him during the brief Polish occupation after World War One. Even so it turns out that Lithuanians have a lot of respect for him and his encapsulation of the desire for national awakening amongst subject peoples. In 1987, at the fag end of Soviet rule, the monument witnessed the first meeting of a Lithuanian patriotic movement aiming to break free from the USSR.

The growing anti-Soviet momentum across Eastern Europe in 1989 only accelerated the protests, and in August of that year activists across all three Baltic states organised a massive human chain. 600 miles long, it stretched down from Tallinn (capital of Estonia) through Riga (capital of Latvia) down to Vilnius. And it ended right in front of the cathedral – in fact, at a spot between the cathedral and the tower…

A new freely-elected Lithuanian parliament declared independence the next year. Nice cuddly Mr Gorbachev wasn’t so happy and eventually sent in troops, but the die was cast and by the end of 1991 the Soviet Union had collapsed.

Now that sounds like a miracle. A social and political miracle. The Lithuanian for “miracle” is Stebukla.

I’m going to end this travelogue by crossing another international frontier. In the meantime, here are some more pictures of the Old Town…

…ending with the renowned but deeply-underwhelming Gate of Dawn, a remnant from the old city walls.

We’ve reached the border. Belarus is a few miles down the road, but don’t worry, this frontier just took me a couple of minutes to reach.

Welcome to the Republic of Uzupis, a district across the river Vilna from the Old Town that declared independence in 1997. It has a flag, president, cabinet, army (since stood down) and anthem, and celebrates its independence day on April Fools Day. Its most famous monument is the Angel of Uzupis.

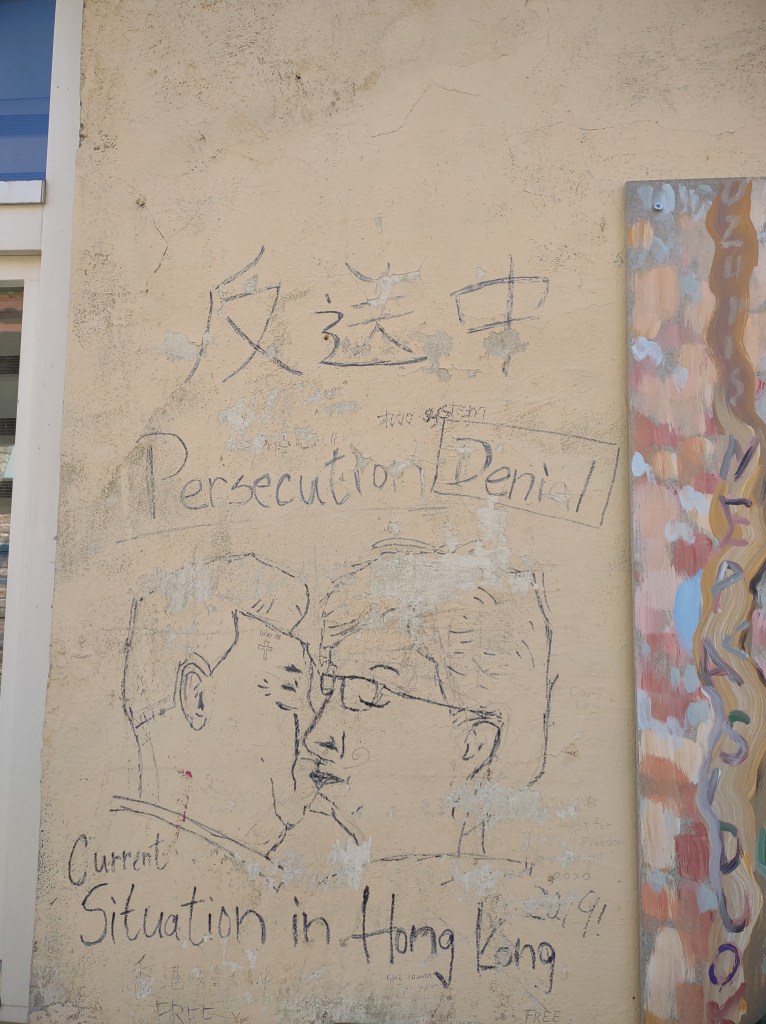

Uzupis was a mainly Jewish area until the Nazis arrived, and it spent the rest of the Soviet era falling into destitution and decline. Artists and arty-types started moving in and…well you can guess the rest. It’s really just a genial and creative bohemian colony bearing comparison to its friends in Montmartre and Christiania in Denmark

Montmartre. There you go.

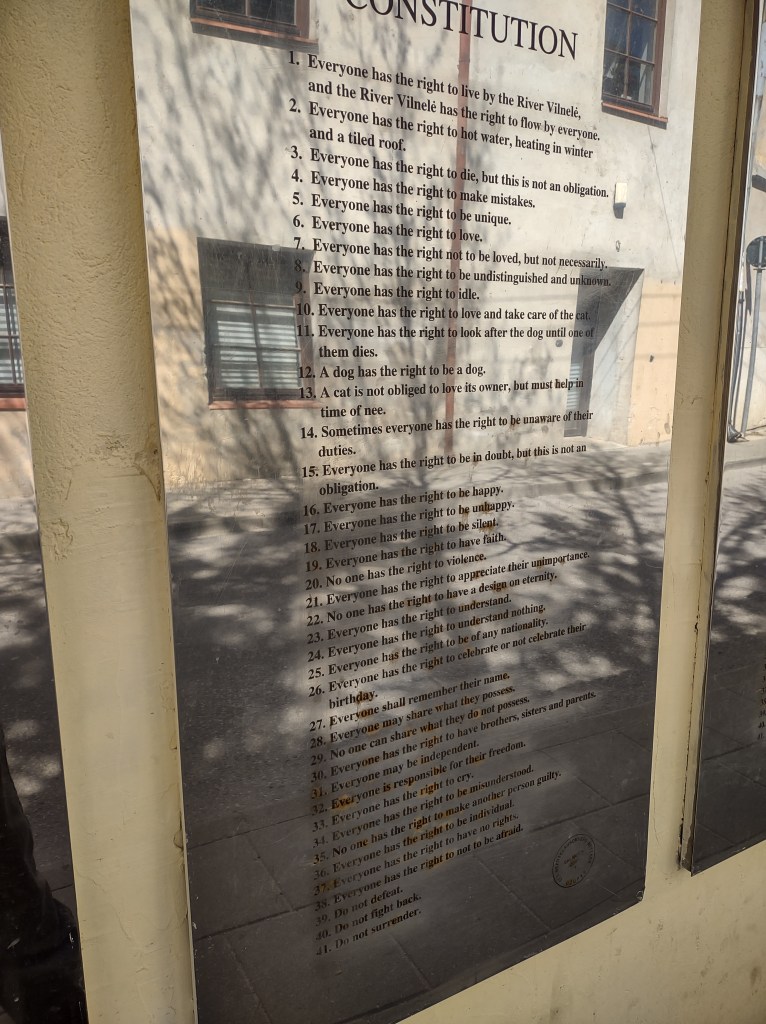

A bit of arty humour, all of this? Well, maybe. There is, however, a constitution. Engraved in forty languages and displayed on metal plates on a street wall, it’s probably Uzupis’s – maybe Vilnius’s – most interesting attraction. And it’s a great way to end our tour.

Some of the rulers in the countries around here, historical and current, would have done well to follow these rules.

(And I don’t just mean the one about the cat)